Savings, and loans

The text is obvious. Homes in the US are big — really big. Everyone has a big home. They're big in city centres, bigger in the suburbs, simply huge in the outer suburbs, still big in remote rural locations. They're also, claims the graphic, growing rapidly — the last panel claims the median home has grown in size by 50% in just twenty five years — interestingly, up to 2007, a date we'll come back to later.

The graphic shows, but doesn't explicitly say, that they're also staggeringly expensive. In New York, where the median size is apparently around 1500 square feet, the price is given as US$1295 per square foot, or about 1.9 million US dollars for an ordinary family house. That's not the extreme — Phoenix, Arizona is shown as even more expensive (why?!?). At the other end of the scale, housing in Dallas, Texas is stated to sell for US$59 per square foot, with a median size of 1650 square feet implying a price of just under a hundred thousand US dollars.

On psychiatry, homeopathy, and the medicalisation of distress

I'm a damaged person; I know that. I know that that damage happened mainly in (and because of) my first six months of primary school. I know that because of that damage, I'm much more vulnerable to stress than most people are — or than I would be if I hadn't been sent to school. I'm now reasonably confident that I will carry this damage — this vulnerability — for the rest of my life, that I will never be free from the risk of another major breakdown, never free from little breakdowns such as the one I had last week.

I'm a damaged person; I know that. I know that that damage happened mainly in (and because of) my first six months of primary school. I know that because of that damage, I'm much more vulnerable to stress than most people are — or than I would be if I hadn't been sent to school. I'm now reasonably confident that I will carry this damage — this vulnerability — for the rest of my life, that I will never be free from the risk of another major breakdown, never free from little breakdowns such as the one I had last week.

In 1998, I broke my back for the first time. As I was driven in the ambulance to Ayr infirmary, I thought it was a foregone conclusion that I would be paralysed; in a wheelchair for the rest of my life. Suppose I had been right. Suppose I had had the spinal damage which would forever prevent me from walking again. Would you consider that an 'illness'? Would anyone?

The answer is clearly 'no'. There's no infectious agent. There's no underlying biological cause. It's damage. Something is broken. It can't be repaired. It's an injury.

Review: Unraveled, by Alda Sigmundsdottir

If I had written a review immediately I finished reading Unraveled, I would not have written this review. But I have been turning it over in my head for a couple of weeks...

If I had written a review immediately I finished reading Unraveled, I would not have written this review. But I have been turning it over in my head for a couple of weeks...

The book is not what I expected. What did I expect? It's explicitly set against the background of the Icelandic kreppa, the meltdown of the banking system, and I expected that the events of the economic catastrophe would interweave with the collapse of the protagonist's marriage, acting, as it were, as a post-modern take on the pathetic fallacy. This doesn't really happen. The two collapses proceed at different paces and don't really counterpoint one another.

Again, the protagonist's husband is the British Ambassador to Iceland. As such he had to be involved in the most startling development in the whole economic mess — the British government's (almost certainly illegal) decision to declare the Icelandic banks 'terrorist organisations' in order to freeze their assets. I had expected the protagonist to see this as a profound betrayal, something which would completely overturn all trust and respect she had for him. Again, it doesn't really happen.

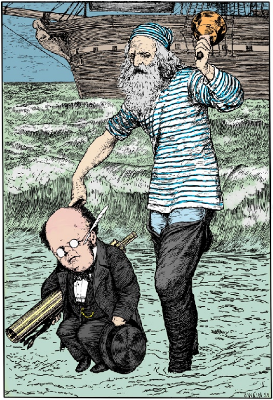

It's time tae rise as levellers again

If you follow this blog, you know already that I am an essayist; you know I'm not a poet. So here is an essay. It's an essay that has been boiling up in me for weeks, and I've been trying to do the background research I need to support it. I haven't fully succeeded in that. There hasn't been time. But now the iron is hot, and I must strike. So here it is: an essay.

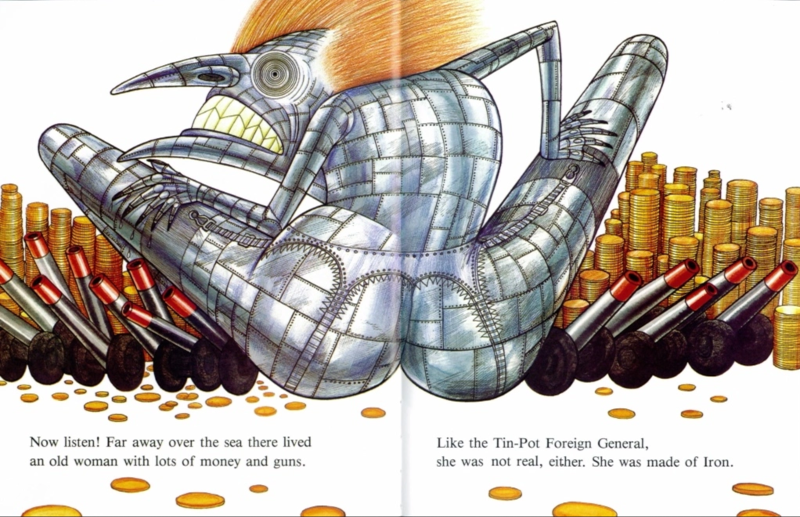

The wicked witch is lately dead

The tower clock is silenced

That else had toll'd her to her bed

Ding Dong. Yet when all's said

Her hagiographers are read

She's cast a saint, her people led

To 'freedom', a land promised —

Her people, not us lesser bred

It's time tae rise as levellers again

Bees, and independence

About ten years ago, when the Scottish National Party was still in opposition (and I was still an active member), I confronted Nicola Sturgeon after a party meeting and told her that if I heard her say 'the minister must resign' just one more time, I'd tear up my membership card and leave the party. We've heard very little of that refrain from the party since; not, I suspect, so much because of what I said (although I hope it helped), as because for a good part of that time the party has been in power.

Don't get me wrong: I still want independence. It's unfinished business. And I honestly think it will make the world (and Scotland) a better place. I still work for it. I still campaign for it. But it isn't, for me, the most important issue on the the political agenda now, by a long way. The most important issue on the political agenda has to be the preservation of the planet as a viable habitat for humans into the future.

That is very challenged at the moment. It's challenged first and foremost by global warming, and the most important contributor to global warming is burning fossil fuels, which makes all the arguments about whose is the oil under the north sea a bit moot. It would be better for all of us if the oil stayed where it belongs, under the north sea, and the carbon it represents was never returned to circulation. But another very significant challenge is ecocide, the accelerating destruction of major parts of the ecosystem which supports all life on this planet. And one of the key elements of ecocide is the genocide of the bees.