By: Simon Brooke :: 23 December 2025

Introduction

This essay grows out of a thread I wrote on Mastodon this morning, which in turn grew out of an essay by Tim O'Reilly on the current state of the 'Artificial Intelligence' industry. One sentence from that essay particularly caught my eye:

By product-market fit we don’t just mean that users love the product or that one company has dominant market share but that a company has found a viable economic model, where what people are willing to pay for AI-based services is greater than the cost of delivering them.

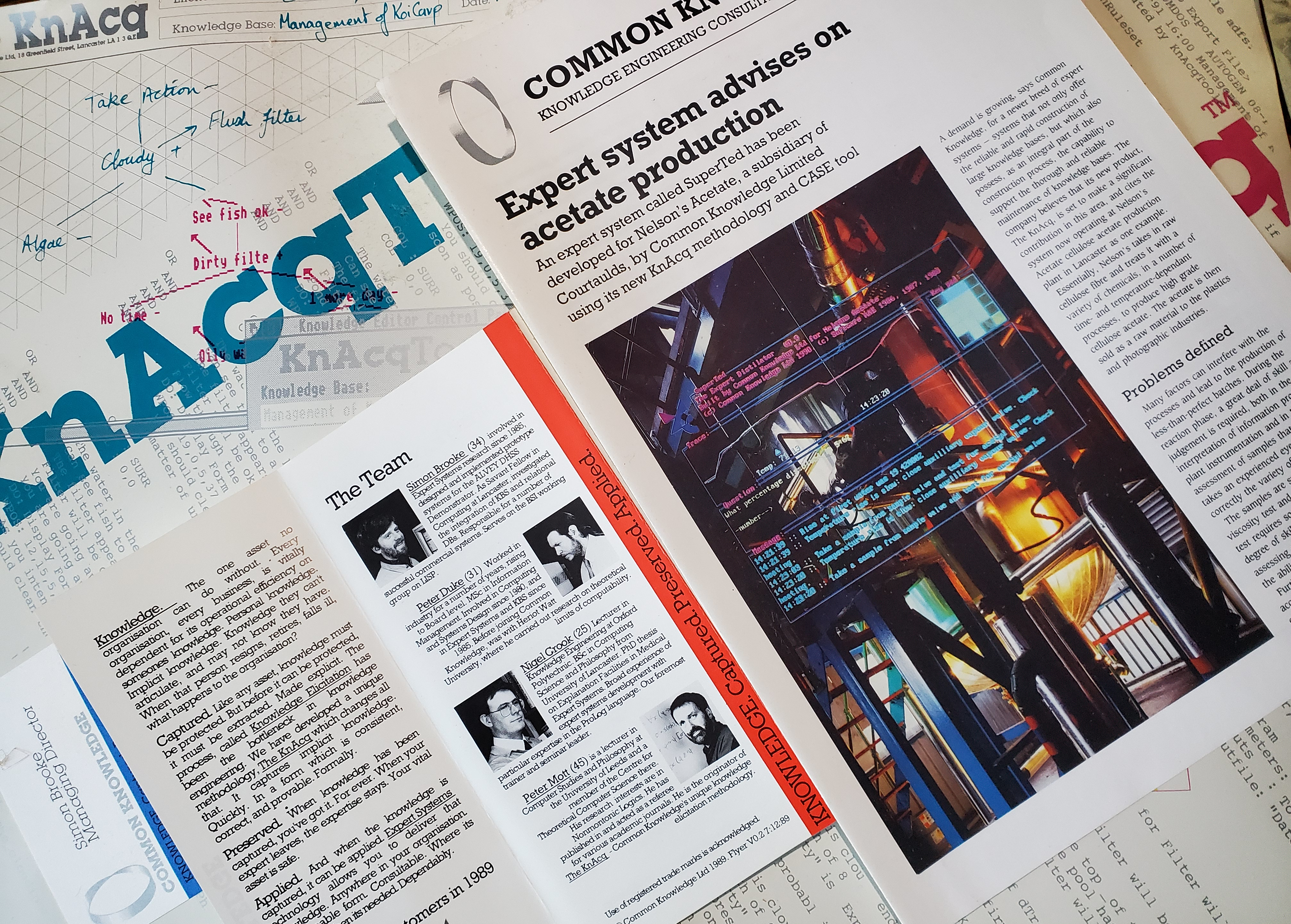

And thinking about that, I pulled in a lot of what I have been thinking recently about the current (third) Artificial Intelligence bubble. I wasn't around for the crash of the first artificial intelligence bubble, but it hurt a lot of people, including people I later knew. The crash of the second artificial intelligence bubble took down the first company of which I was CEO, and I still think that was a potentially good company.

We had a real product, which did real and useful things, although I acknowledge it had teething problems. It ran very well on a very niche platform, but the port to UNIX had persistent memory leaks which we failed to fix. Nevertheless if I had had better mentors, if I was myself better at social networking, I think that company could have survived.

But I was elected, by my colleagues, to lead that company, because I was the person who had done a great deal of the work in building the knowledge elicitation toolkit and inference engine on which the product was based, and had designed and written the compiler which allowed it to export its knowledge bases to many of the then-popular 'expert system' inference engines. I do know a bit about AI, and about the business of running an AI company.

O'Reilly's main argument in his essay is that either Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) will happen soon, in which case OpenAI's business model makes sense (and every other business is in deep trouble); or else that it won't work, but that businesses within the current AI sector will develop broad AI capability that offers real cost-benefit to its consumers.

I think he's way too optimistic.

Let's go back to the quote — his quote — that I opened with: AI companies can only be profitable if '...what people are willing to pay for AI-based services is greater than the cost of delivering them'. Just so. Think about that. The compute cost of training a Large Language Model is phenomenal. Once it is trained, the cost of running a single transaction through it is pretty substantial, compared to, for example, a complex database query. These services cost massive amounts of money to run. They're only worth running at all if they save phenomenal amounts of money for their customers.

We've as yet seen no evidence that that is true of LLMs for any substantial market sector. On the contrary, MIT reports that:

Despite $30–40 billion in enterprise investment into [Generative AI], this report uncovers a surprising result in that 95% of organizations are getting zero return

Let's be clear about this, I believe that Artificial General Intelligence is possible, and that given enough well-directed effort, it can be achieved. I think that On Computable Numbers gives a clear, formal proof that that is so. But I don't think we're on the road to it at present, and I don't think any of the present well-known AI businesses will achieve results which actually provide any cost benefit.

The Problem

We've had niches where AI had real cost benefit since the 1980s — I've designed and led teams on some such systems myself — but they're rare and they're point solutions, not cheaply generalisable. Extracting and codifying human knowledge into a form that a machine can infer over is itself a craft — one which my team partially automated, but still time consuming.

Today's 'Stochastic Parrots' — Large Language Models, or LLMs — offer no cost benefit, except in domains where accuracy truly does not matter, and those are rare. In every other domain, the cost of checking their output is higher than the cost of doing the work. This is perhaps especially true in the domain of software development, because being able to debug problems in code depends to a great extent on deep understanding of that code, and of the intent behind it.

But in a broad range of domains, from self driving vehicles through medicine to legal decision making, being wrong matters. If a machine spits out the wrong answer, people may be killed, or imprisoned, or suffer severe financial or reputational losses. To check the output of the machine, you need enough specialist knowledge to have made the right decision for yourself. And you only learn that degree of knowledge through practice.

The impedance between rule based 'old AI' systems, which had a degree of ontology encoded into their rules, and neural net based, 'new AI' systems which include LLMs, is that in the new AI systems the knowledge is not explicit, and is not (yet) recoverable in explicit form.

Consequently, we can't run formal inference over it to check whether the outputs from the system are good, and neither can the systems themselves.

It's not impossible that that could change. Some hybrid of an LLM with a robust ontology must be possible. It's not impossible that systems could be built which could construct their own robust explicit ontology; but that's a research field in which there have not yet been any breakthrough successes.

Otherwise, building a general ontology is a very big piece of work. It has been attempted, and in some domains domain-specific ontologies are fairly well advanced. Linking these and (vastly) extending them to make a general ontology is a huge piece of work, but it's possible work. We know, at least in principle, how to do it. They can be built and will be built, and, because they are explicit, will be relatively easy both to maintain and to extend.

But, the impedance between the LLMs, with their cryptic, unverifiable knowledge, and explicit ontologies, will be a very large one to bridge.

It's my view that it is easier to build language abilities on top of an explicit system (I know how to do this, although it would not be as fluent as an LLM) than to bridge that gap.

A system which has robust knowledge about the world can test the output from an LLM and check whether it passes tests for truthiness. This is, after all, sort of like how our own minds work: we leap very quickly to solutions, which may be wholly fallacious; but if we have time and wisdom, we will test those solutions against our existing knowledge to evaluate whether they are trustworthy

Note that, every intelligent system should be operating in domains of uncertain knowledge — in domains where knowledge is certain, an algorithmic solution will always be computationally cheaper — so it is possible for an AI to be both good but sometimes wrong.

However, a system with real intelligence will know where it could be wrong, and what additional data would change its decision.

Again, this is not rocket science. We had such systems — I personally built such systems — back in the 1980s. The DHSS large demonstrator Adjudication Officer's system — which I built, and which is described in this paper — did this well.

My (unfinished) thesis research was on doing it better.

There's a claim that artificial 'neural networks' model the mechanisms of our brains. I don't believe that is true. I don't believe we yet understand enough about how our brains work to produce good functional models of them; but in any case, our present generation of neural networks, with their very small number of layers, model only a very simply sort of brain. The brain of an insect? Possibly. Of even the most primitive mammal? I am really not persuaded.

Intelligence and consciousness

Obviously, the human brain doesn't do formal logic very well. Western ideas of 'intelligence' are largely based on the idea that the ability to do formal logic is a high indicator of intelligence. Inference engines are excellent at formal logic, but don't (yet) have the ability to learn. The ability to learn is also seen as a high indicator of intelligence.

An inference-based system which could generate and test new rules, and increase its confidence in those new rules to the extent that they proved valid in practice, is perfectly feasible, and there are many examples of such rule induction systems in the literature. The new rules generated by these systems are explicit, and therefore can be presented to human checkers for review; unlike knowledge learned by neural nets, which, so far anyway, can't be.

Consciousness is something which we believe we recognise when we see it. I don't have a formal definition of consciousness against which a set of tests could be developed. A theory of mind is clearly a prerequisite, and I am confident that I could build a system which could model its own and others' behaviours and infer about those models; the game-theoretic inference system which is the core of Wildwood essentially does this. But it doesn't seem to me that such a system would exhibit consciousness.

I don't see how consciousness could emerge from system based on an inference engine. I could be wrong about this, but I think that an inference plus rule induction system, although it is likely produce useful intelligent behaviour, is unlikely to ever to produce consciousness.

By contrast, we believe that the human brain displays consciousness; it is, in fact, our exemplar for consciousness. And we strongly believe that its essential architecture is a sophisticated neural net. So there is strong evidence that a neural net can display consciousness.

Conclusion

My personal opinion is that LLMs are largely an evolutionary dead end, and that as they increasingly feed on their own slop, the quality of their output will deteriorate, not improve. I'm not the only person to think this. I firmly believe that Artificial General Intelligence is, as I've said above, possible; but I believe that if it is to be achieved in the near future, will be ontology plus inference based, rather than LLM based.

This isn't to say that neural nets are necessarily an evolutionary dead end; obviously, the human brain is some sort of neural net, and it works to some extent. It obviously isn't super-intelligent, but if a more intelligent variant could be evolved and would have evolutionary benefit, it would have evolved.

What will be needed if neural net based systems are to develop real intelligence, however, in my opinion, is not throwing huge amounts of unstructured data at very simple neural nets. We've tried that, that's what large language models are, and we know enough about them now to know that that path does not lead to (any) intelligence. What would be needed is understanding how to build more sophisticated neural net structures. Ultimately, if our aim is to reproduce consciousness rather than merely intelligence, I think this is likely to be a more fruitful avenue of research than a pure inference based approach; but I think it is a much longer project.