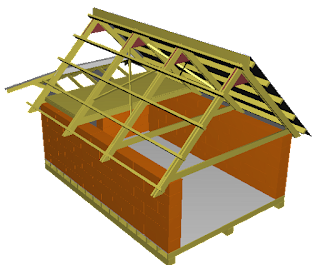

Building plan for the Winter Palace

If the bothy I'm wryly referring to as the Winter Palace is to be built in one weekend — hopefully in one day — a lot of preparation has to be done first. Let's start with the basics: materials.

The winter palace comprises straw bales, timber, render, insulation and a few other things. It would be elegant if the straw bales came from barley crop and, in theory, they might. But I'm not confident that my barley will be ready to harvest in time, so it would be prudent to get bales from another source. Similarly there would be a lot to be said for using timber from my own wood; in terms of energy and the environment it would be the best solution. But I'm not at all confident we can mill enough timber in time and even if we do it will be horribly unseasoned. So, again, it may be prudent to buy the timber from the builders' merchant.

Towards a farming plan for the West Croft

My objective for farming the West Croft is to essentially make as large a contribution to self sufficiency as possible, while minimising cash inputs. I'm not significantly concerned with maximise cash profit, although I can't afford for it to become a major cash drain.

I intent to continue to farm the croft as organic, not so much because I believe in the benefits of organic food but because I want to maximise biodiversity and minimise long-term environmental impact. It's no great advantage to me for the croft to be registered organic, since the difference in profit between certified organic production and uncertified production is unlikely to cover the cost of registration, but if the croft continues to be covered by the Standingstone registration that is in my interests.

These objectives need to be balanced against constraints.

On heiding thistles

But mark the Rustic, haggis-fed,

The trembling earth resounds his tread.

Clap in his walie nieve a blade,

He'll mak it whissle;

An' legs an' arms, an' heads will sned,

Like taps o' thrissle.

The symbols we choose tell us something about how we see ourselves, and, perhaps, a little of how we really are. Only in Scotland would we seek to extirpate our national flower. Only in Scotland would we celebrate a poem which speaks of doing so. Only in Scotland would we be utterly confident that we will never succeed.

The state of social media

Vision

You post to the social media system of your choice. Your friends — the friends you choose and no-one else, unless you choose to make your post public — see it on the social media system of their choice. If they choose to respond, they respond to a common thread which all your friends (and possibly theirs, if you've allowed that) can see, limited by the specific capabilities of their chosen system. For example users of one system might see the discussion as a branching threaded discussion like Usenet, while others see a single unbranching thread. Common conventions for tagging, reposting and referencing other users are used across heterogenous social media systems.

Impossible? Technically, no.

Haymaking

It's been a big week here on the farm; so big, a journal entry is required. But so big too that, here in the lull that follows, my memory is already confused. I'm setting down events as I remember them; I could be wrong.

The core of it has been hay. We decided, early in the year, to put the majority of the farm down to hay as needing least work. We all knew that this would be a busy year...

We've needed to harvest the hay for a while; it's been ready. Finn had bought — out of his own pocket, as his own property — the basic equipment needed: a mower, a hay-bob, a baler. All of them were old, second hand, sold, in fact, as scrap. But Finn, our smith, is talented with metal mechanisms, and he fettled them up and made them work.